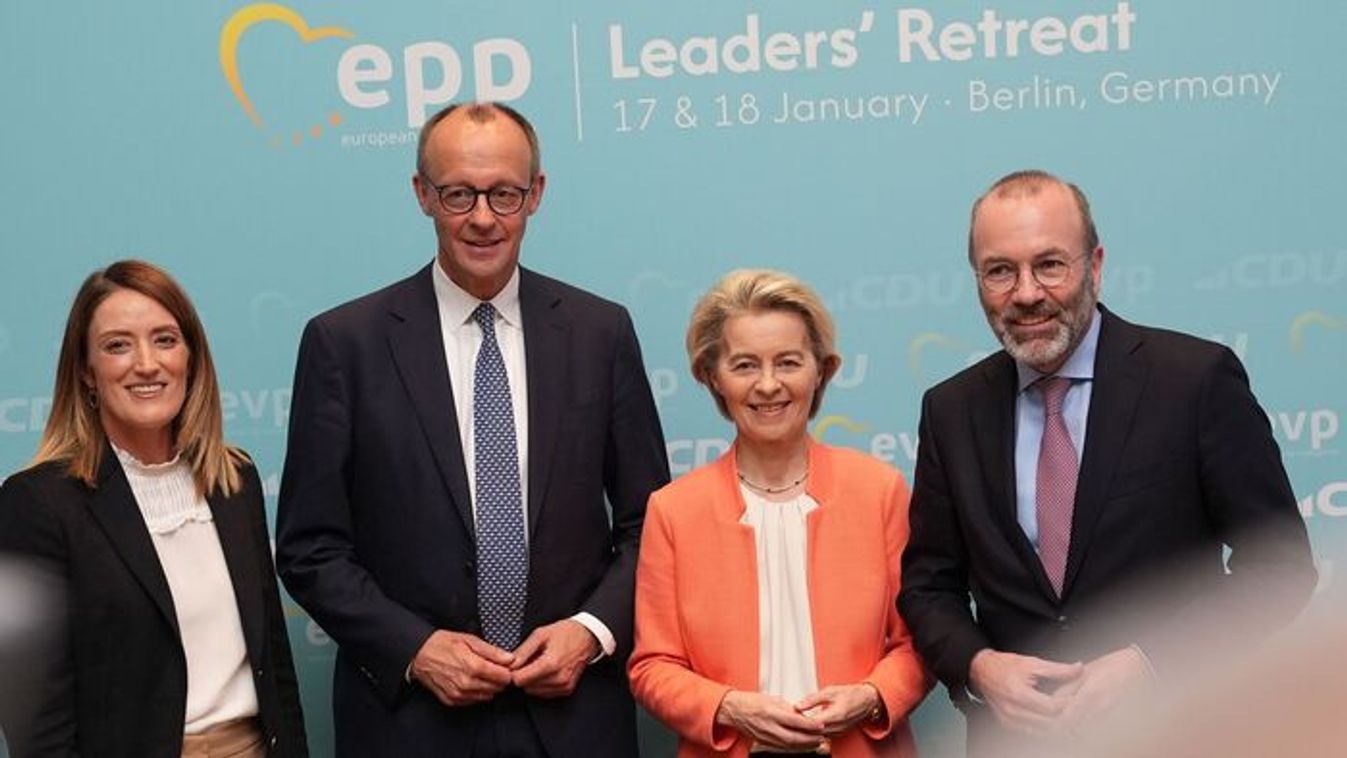

Két út áll az Európai Unió előtt: az egyik a történet végét jelentené

Egyre világosabb, Orbán Viktor miért hangoztatja régóta, hogy a brüsszeli politika irányát meg kell változtatni.

CNN Travel recently recommended the Budapest Marathon, held annually in October. Returning health enthusiasts and their heftier (and saner) counterparts will be greeted by some new sights adorning the Hungarian capital. Naturally, a big metropolis lives in constant flux. However, in the last few years significant changes have taken shape here.

During the post-1989 transition period, Budapest trudged along in its large, grey manner, a city of more than two million inhabitants that preferred cars to pedestrians on its motor-oriented streets. This urban developmental style applied across the metropolis, even to the downtown area. After 1990, the post-modern movement dominated emerging innovations for almost twenty years. New buildings that attempted to mesh with the classic style of their older surroundings were dismissed as mere historicism and regression. Developers maintained that each era has its own style, and that society shouldn't force architects to copy the past. That era, named for the Budapest mayor of the time, Gábor Demszky, aimed to created something remarkable of its own.

In 2010, the new leadership of the city adopted a different philosophy. Mayor István Tarlós, who had formerly managed a large suburb district during the Demszky-era, was known for his pragmatic, step-by-step politics. The mayor began with the modest project to repair Budapest and efficiently maintain its infrastructure. Tarlós originally avoided plans to make any sweeping changes to the capital. However, under the guidance of this fresh leadership, these reforms ultimately blossomed from the practical into the truly remarkable. The Budapest mayor wasn’t the first and only driving force behind transformation. Innovations in the city center began as early as 2006 when Antal Rogán became mayor of the 5th district, the heart of downtown Pest (Budapest is composed of districts, each with its own municipal government like the arrondissements of Paris).

Like many urban areas in the West at the time, most innovations under the communist government were geared primarily toward automobiles and their drivers. Now the trend swings the other way, giving the streets back to the pedestrians – at least in downtown Budapest. People enjoy more and more crosswalks and pedestrian-only streets. Gone are the days where pedestrians were merely considered obstructions to motorists.

One of the latest grand projects got underway in November 2012. Ferenciek tere – or Franciscan’s Square, named for the Franciscan church that stands on its southeast side – has been split into two parts since 1973 by a tunnel for cars. This tunnel is now being dismantled, along with the major thoroughfares of Kossuth Lajos út and Szabad sajtó út, which connects traffic to the Erzsébet bridge. Franciscans are contributing to the new look as well with the renovation of their baroque style church where Ferenc Liszt once regularly attended Mass. One of the square’s iconic twin palaces are among several buildings also is renovated.

One of the oldest squares in Pest is located in the Ferenciek tere neighborhood, Március 15. tér (or, March 15th Square, which commemorates the revolution of 1848) and boasts a beautiful panorama of the Danube and Buda. The church in the square preserved the last remnants of the Middle Ages on the Pest side of the capital. Despite the historical significance of this site, which also houses ruins from the Roman Empire, the square was long a pale and dilapidated area, populated by vagrants preying on the wallets of tourists. Today, the renovations have transformed the square into a shining and vibrant jewel of the area once again. The improvements have also reached Kecskeméti utca, previously a narrow road crowded with cars at the beginning of the 15 kilometer-long avenue called Üllői út. Just a few steps away is Széchenyi István Square, which is also slated for renovations soon. Kálvin Square was given back to the people by the end of 2010, an important meeting point for university students due to its close proximity to one of the most popular libraries in addition to several universities. The semicircle of the kiskörút, or Small Ring Boulevard, including roads around the innermost center and its tram were also renovated, presenting a new and greener city landscape.

Future improvements and extensions of other tramlines are in the works as well as the renovation of the stalwart holdout, Széll Kálmán Square (formerly Moszkva tér, or Moscow Square), one of most important transportation hubs on the Buda side. Bigger and more ambitious yet is the renovation plan for the royal palace of Buda and its gardens. Some parts of the royal palace have been abandoned since the 1980’s and have fallen into serious disrepair. This project is expected to span the course of several years and involves coordination with the national government.

Budapest is known as the “city of spas”, but local and international 20-somethings know and enjoy the city's so called “ruin pubs”, night spots housed in older, rundown building of (usually) downtown Pest. The rising popularity of these downtown nightspots has provoked conflicts between the locals and the young revelers. Given that Budapest is the seventh biggest city in the European Union, the notion that calm and quiet will reign throughout the center of this busy metropolis is probably not realistic. However, local authorities in certain districts are encouraging pubs and shops that sell alcohol to adhere to tighter restrictions and operating hours (closing hours as early as 10 p.m.) in an effort to curb street noise in these neighborhoods. Because the popularity of Budapest is partly due to its vibrant nightlife, the new regulations were not popular among club owners, the staff and, naturally, the patrons. It will be difficult to please everyone.

The Hungarian-American historian John Lukacs wrote in his book Budapest, 1900: “the Hungarian capital lived its best days with vibrant cultural life and prosperity around the beginning of the last century.” I like to think that if he had written this book today, he would speak of the recent return to human creativity and vibrant spirit we’re witnessing again in the streets of Budapest.