Ez is napvilágot látott: Magyar Péter tudhatta, milyen bosszút forralnak Magyarország ellen

A szakértő szerint közölték a Tisza Párt elnökével, mi a feltétele a hivatalban maradásának.

“Central European countries such as Hungary can benefit from the rise of Asia by focusing on targeted niche areas where it enjoys comparative advantage to complement the supply chain in Asia, which is undoubtedly turning into the factory for the world” – Darius Chan, Director, SMU Law Academy pointed out in a conversation with Lénárd Sándor.

Asian countries have been increasingly attractive destination of foreign investments as well as for commercial transactions in the past decades. This growth is due to a number of factors including the technological and transportation developments, the liberalization of trade and investment regimes along with the subsequent large production and consumer markets in Asia. How has this development influenced international investment and commercial arbitrations that are linked to either Asian countries or Asian businesses?

To attract foreign investment, there has been a proliferation of bilateral investment instruments across Asia between the 1980s to the 2000s. For instance, it has been observed that more than 360 bilateral investment instruments involving Asian and Pacific countries were signed in the 1990s and more than 240 bilateral investment instruments were signed in the 2000s. One can therefore argue that these bilateral investment instruments have arguably played a role in encouraging foreign investment into Asia.

However, it has also been observed that the number of new bilateral investment instruments fell dramatically after 2010. Two reasons have been offered. The first is the global backlash against investor state dispute settlement (“ISDS”), and secondly, many Asian countries have emerged as significant exporters of capital themselves, such as China and Japan.

As a result, what we are now witnessing is what I would call market consolidation, where

Asian countries are shifting away from bilateral instruments towards multilateral instruments,

such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) in 2018 and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in 2020. I would expect the next generation of disputes will be governed by mechanisms negotiated under such multilateral instruments.

What advantages do these multilateral instruments offer compared to bilateral ones in terms of dispute settlement for example?

The verdict is still out on this question.

The global backlash against ISDS has led drafters to re-think the dispute settlement provisions in new multilateral instruments.

For instance, it was reported that because the inclusion of an ISDS mechanism during negotiations of the RCEP was controversial, that has been left out in order not to delay the conclusion of the RCEP. Signatories to the RCEP have agreed to further negotiate the ISDS provisions but any amendments to the RCEP would require the approval of all signatories. In the meanwhile, disputes may be referred under an inter-state dispute settlement mechanism instead, which harks back to the times of diplomatic espousal. As we know, it will be difficult for investors to know for sure whether the home state of the investor will necessarily commence proceedings on the investor’s behalf, especially given the political realities of competing priorities and administrative bureaucracy.

One significant difference between the Western, both civil and common law legal tradition and the Asian legal culture is that the latter reflects a harmony seeking social culture which core idea is the “consideration of others”. So, the litigation practice and the mission of the judiciary are driven by the desire to reach settlements. How could you reconcile this attitude with the Western conception of international investment and commercial arbitrations that consider litigation as a fundamental right? Is there a tension between the arbitration clause of international investment and commercial treaties and the Asian judicial conduct?

It has been said that, in certain Asian cultures,

the signing of a contract marks the start of an evolving relationship of give-and-take for mutual benefit, rather than a fixed declaration of rights and obligations.

Having said that, in my own experience, business parties and their legal advisors, whether Asian or not, are increasingly looking to settle disputes, and the commencement of formal proceedings is typically seen not as an end unto itself, but a form of leverage as parties negotiate a settlement in parallel. Similarly, although there are varying differences between jurisdictions, in my experience, courts and tribunals in major jurisdictions are increasingly comfortable doing what they can to facilitate settlement between the parties.

The international investment regime has been widely criticized in the past decade since it favors a business interests at the expense of public interest regulation of the States. How do Asian countries view these criticisms and what are their experiences in this regard?

Indeed, Asia has not been spared from this global backlash against ISDS, with countries such as India, Indonesia and Australia intimating their intention to resile from the ISDS regime. What is more interesting may be the response to mitigate some of the perceived shortcomings of the ISDS regime. For instance, it has been observed that there is a greater use of binding statements and interpretation for states to issue joint interpretations of treaty provisions. There are appellate mechanisms being contemplated in some investment instruments, including a permanent investment tribunal. Some states have also established judicial bodies to serve as alternatives to the ISDS regime.

Singapore itself was a key mover behind the Singapore Convention on Mediation,

which in my view has contributed significantly to raising the global awareness of mediation, including in investor-state disputes.

The Singapore International Commercial Court (SICC) started its operation in 2015 offering venues for both commercial and investment arbitrations. That might signal a shift away from the traditional Western oriented arbitration centers such as the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce, the Paris based International Chamber of Commerce or the London Court of International Arbitration. How do you see the significance of the SICC?

The

SICC ingeniously seeks to combine the best aspects of arbitration,

for instance, procedural flexibility, confidentiality, emphasis on party autonomy with

the best aspects of litigation,

for instance, greater control over timelines, greater control over multiple parties and multiple contracts, and the availability of an appellate process. This is coupled by assembling the best international judges in a English-speaking city state eco-system where many international companies and law firms operate. However, a current challenge that the SICC faces is the notion that SICC judgments are more difficult to enforce than arbitral awards. As the track record on the enforceability of SICC judgments grows, my own view is that business parties will increasingly accept the SICC as a viable option, especially for contracts involving Asian parties.

Another ambitious initiative is China’s Belt and Road Initiative that aims to somehow revive the “Silk Road”. How do you view this development?

The sheer amount of capital invested should bring about significant improvement in the infrastructure development of developing states along the Belt and Road. For lawyers, an important legal aspect of the Belt and Road Initiative (“BRI”) is the creation of judicial bodies and arbitral institutes, including the China International Commercial Court (“CICC”), and it will be interesting to see the extent to which the market will embrace the CICC as an arbiter of BRI-related disputes.

The BRI also means an increase in outbound Chinese investment,

and therefore one should not be surprised to see an uptick in cases where Chinese investors will pursue claims before various fora. At the very least, this will call for the international community, including businesses and their advisors alike, to have a greater understanding and appreciation of the business culture in China, for purposes not just for dispute resolution, but for dispute prevention in the first instance.

It seems that there is an increasingly robust economic interconnectivity and improvement in Asia. How can a Central European country like Hungary benefit from this development?

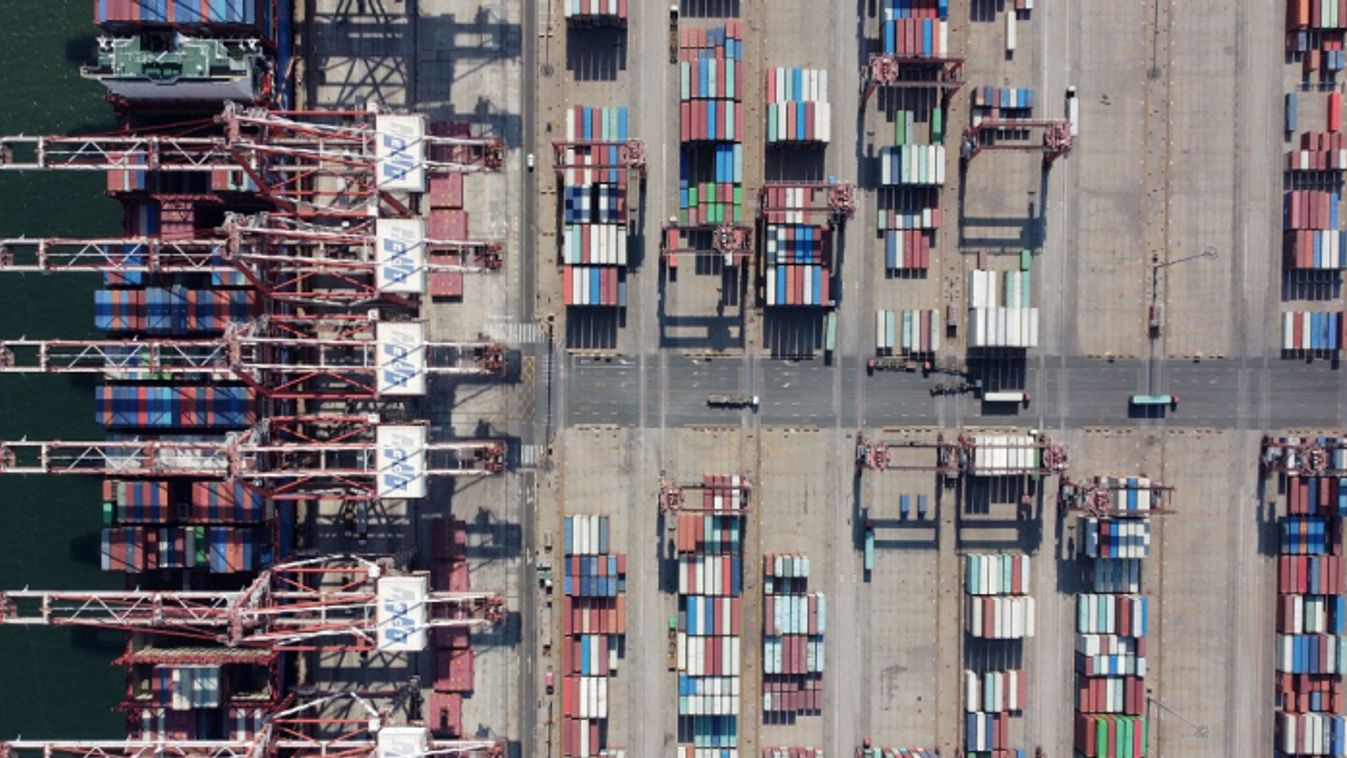

In my view, Central European countries such as Hungary can benefit from the rise of Asia by focusing on targeted niche areas where it enjoys comparative advantage to complement the supply chain in Asia, which is undoubtedly turning into the factory for the world.

Greater outreach and interaction between trade bodies and associations to explore potential areas of synergies will be particularly timely

as the supply chain recovers from the pandemic. Greater outreach need not necessarily take the form of physical travel, but can include sophisticated use of online platforms and mobile applications to connect with potential markets in Asia.