Kellemetlen: elhangzott az eddigi legfontosabb mondat Magyar Péter rejtélyes videójáról

Bár a drogos bulibotrány nagyon zavaros, az biztos: Magyar Péter zsarolható – mutatott rá az elemző.

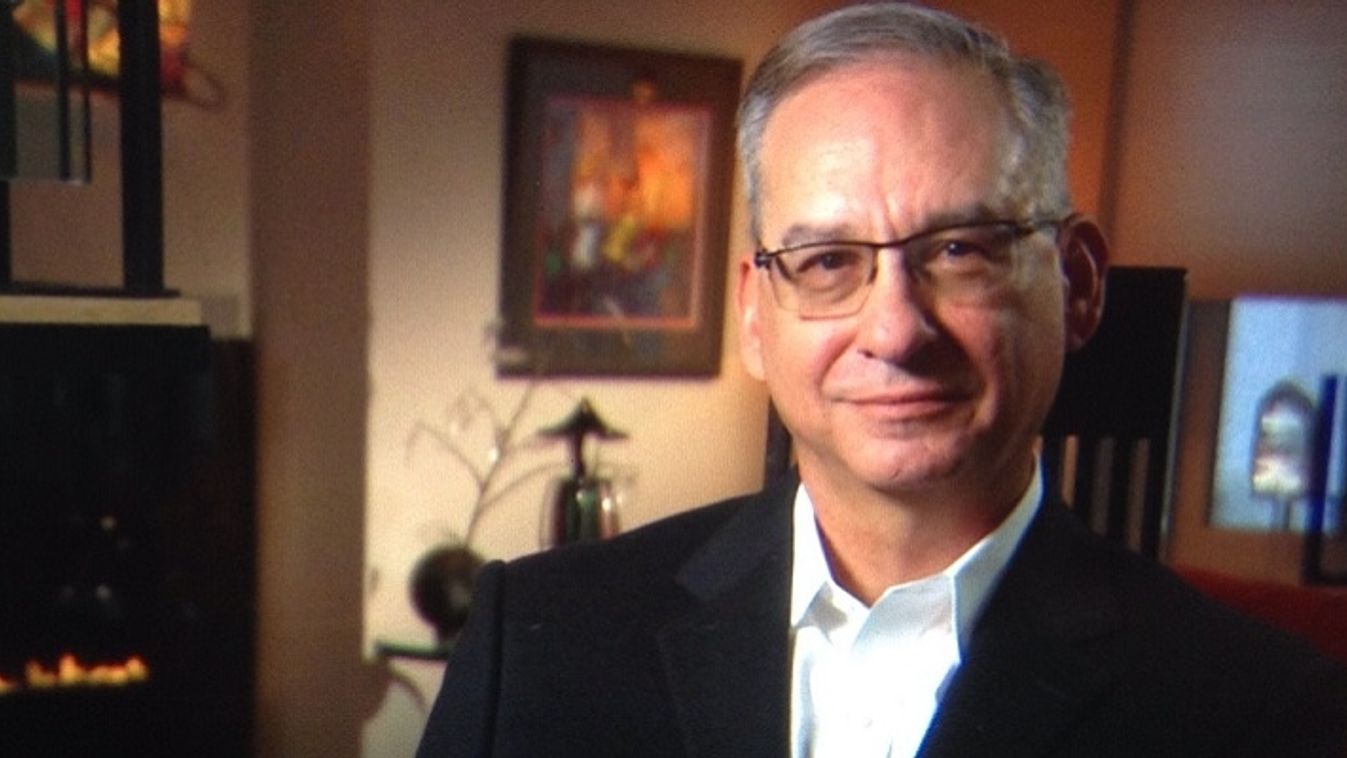

Instead of a “Lockian” society in which the government exists as the servant of people to protect the rights of individuals, centralization creates a kind of “Hobbesian” war. Once a “Leviathan” is created, you have to fight a “holy war” to control it because if you do not control it, then your political opponents would control it - says Randy Barnett, Professor of Law at Georgetown University during a conversation with Lénárd Sándor, researcher at the National University of Public Service in Hungary.

Lénárd Sándor: I am honored to greet Randy Barnett who is the Carmack Waaterhouse Professor of Legal Theory at the Georgetown University, where he directs the Georgetown Center for the Constitution. Professor Barnett is amongst America’s leading scholars of constitutional law. Professor, you are the author of the fascinating and superb book Our Republican Constitution: Securing the Liberty and Sovereignty of We the People in which you outline two competing visions of the American constitution. Can you introduce us to these two concepts? How did they evolve throughout the history of the United States?

Randy Barnett: I thank you for including me in your interview series. These are two conceptions of what constitutes a good constitution. These are based on two conceptions of popular sovereignty based on two conceptions of “We the People”: the collective and the individualist conceptions of We the People.

At the time of the Founding, political theory of the time required you to locate who the “sovereign” was in a particular polity to identify who had the right to rule. The law was directly or indirectly a product of the will or desire of the sovereign. Once the Americans had cast off the English monarch as their sovereign ruler, who was now the sovereign? Popular sovereignty was an idea the Founders developed to answer this question.

In American, it is We the People who are the ultimate sovereign.

But how is this to work? If the function of sovereignty is to specify “who rules” the people, and “the people” are the ultimate sovereign, this seems to be incoherent. And what is the sovereign “will” of multidute of persons comprising We the People?

One way to reconcile this incoherence is to read “We the People” collectively or as a group, which leads to a collective conception of popular sovereignty. The “will of the people” cannot be the will of every person; it can only be the will of a majority of the people. So this means that a good constitution is a democratic constitution that reflects the will of “We the People” as a group, which translates into the will of a majority of the people.

If you hold this vision of popular sovereignty, then judges—who are unelected and do not represent the will of the people and are not accountable to the people—should not interfere with the will of the democratic majority as reflected in the representative assemblies or legislatures—except perhaps for very exceptional circumstances. This vision of popular sovereignty is so commonplace that I think your readers cannot imagine that there is any other conception. But there is.

The other vision of popular sovereignty is individualist, based on “We the People” as individuals, each one of whom has the inalienable natural rights—in the words of the Declaration—to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. (Notice that each of these rights are possessed by individual people not by the collective body of the people as a whole.) Now, if “We the People” consists of individuals—that is each of every one of us—and if each of every one of us possesses natural rights that precede government, then the fundamental purpose of government is to secure these rights. And sure enough, to the very next sentence of the Declaration of Independence says “that to secure these [individual, natural and inalienable] rights, Governments are instituted among Men. . . .”

Under this vision of popular sovereignty, we distinguish between the governed and the governors or government. Indeed, the Declaration says that “Governments are instituted among Men,” which means they are a subset of the people. And these governments “deriv[e] their just powers from the consent of the governed.” So what then does it mean to say that “We the People” are the ultimate sovereigns?

“We the People” are sovereign because “We the People” are the ultimate masters and the people who make up the government are servants. We the people have rights, and governments “are instituted to secure these rights.” Governments have only powers not rights and their “just powers” are limited to the securing of the rights of the sovereign masters: We the People.

So the measure of good governance is whether they are able to effectively secure the rights of the people or not. Elected representative bodies are important—not because they represent the “will” of a collective people, which is a complete fiction. That legislatures are elected is important to provide a poplular check on government power. People can vote out their rulers rather than overthrow or assassinate them.

But, in addition to that, an independent judiciary is also important to check those elected bodies so that they stay within their “just powers” and do not violate the inalienable rights of “We the People.” In my book, I called the first conception the Democratic conception of the Constitution, while I called the second one the Republican conception of the Constitution. This is not a reference to the current Democratic or Republican parties. It is a reference to two different conceptions of We the People, which lead to two different conceptions of popular sovereignty that lead to two differenct visions of a good constitution.

L. S.: And what are the most important implications of these two conceptions of the constitution in today’s’ America? Can the republican conception of the Constitution protect Americans from the danger of an omnipresent government and an omnipresent regulation?

R. B.: Our Constitution is Republican and not democratic in the sense I am using the term. A democratic representative Congress is only one part of a larger structure that is intended to protect the rights retained by the people. This structure includes for example the separation of powers between the two houses or chambers of the Congress, between the Congress and between the executive branch, and an independent judiciary that keeps the other branches in check.

It also means limiting the legislative powers of Congress so the rest of the powers are exercised by fifty different states, which we call “federalism.” The existence of these fifty different states in the United States preserves diversity and competition amongst states for devising and implementing good policies, while competing also to protect the rights of “We the People.” In Europe this principle is called “subsidiarity” because local issues should be handled by local officials.

The reason why this is so important today is that each of the “non-democratic” or structural elements of the Constitution—like the Senate, or the Electoral College, or the Supreme Court—is under attack by people who are accusing each of these institutions as “undemocratic.” The point of my book is that they are good because they are undemocratic in the sense that they are not majoritarian. Rather they put limits on the powers of the majority so that neither a majority nor a minority can easily violate the rights of the individual.

L. S.: But some experts also say that unreasonable judicial activism threaten to stifle the democratic decision making process of states. The United States witnessed a period of time throughout the 1960s and ‘70s when a progressive and activist Supreme Court read and imposed controversial and sometimes unpopular rights on the national as well as on state governments. How do you see the danger of judicial activism?

R. B.: “Judicial activism” is a tricky term. On the one hand it can refer nonpejoratively to whenever a judge invalidates a “popularlyly-enacted” statute. If so, then anyone who thinks that judges should ever invalidate unconstitutional laws—which is nearly everyone—favors “judicial activism” sometimes. On the other hand, it could be used pejoratively to describe a circumstance in which judges improperly interfere with the legislative process by invalidating laws that were valid and should have been upheld.

But this latter view of “judicial activism” requires—and usually simply assumes—an explanation of why the judicial invalidation was wrong based on the substance of the law being invalidated. In other words, to apply the pejorative “judicial activism” to a particular decision requires the critic to explain why the decision was wrong on the merits—not merely that it was an unelected judge invalidating a law that reflected the “will” of the people through their representatives.

Of course some of the sting of the pejorative is removed once we realize that legislators and judges are both merely servants of the sovereign people and neither’s views necessarily represent the “will of the people.” In our system, both judges and legislatures are bound by the law that governs them: the written Constitution.

When Congress exceeds its just powers, that is “legislative activism”; when judges do it, we can call that “judicial activism.” But we should be careful not to let the labels do all the work.

L. S.: Speaking about the separation of power, the principle of Federalism and the autonomy of member states are also considered as part of the system you call “checks and balances”. How do you see the famous formulation of the late Justice Louis Brandeis who saw states as “laboratories of democracies”?

R. B..: Louis Brandeis was a famous progressive and the “laboratories of democracies” he had in mind were laboratories of regulations that are all different ways of experimenting with how to regulate the people. Once you discover how to regulate them at the state level, then you should regulate everybody at the national level accordingly. So this idea was inimical to the idea of protecting individual freedom.

Unfortunately, what has developed and still exists in the United States is the so called “cooperative federalism.” Because of the broad taxing power of the federal government, a state’s residents can be taxed with a federal income tax and this money can then be used as an incentive to induce states to regulate in a way the federal government desires. The states then become supplicants at the feet of the federal government who are taxing away the states’ residents’ revenue. Notice that, if the state turns the money down, then it goes to other states. Therefore, politically it is very hard for a state to turn down the money that has been taken from their own residents, and let that money benefit residents of other states. This is one of the most effective ways for the federal government gets the states to regulate in ways that may be beyond the powers of Congress.

L. S.: Speaking of extensive federal government, one of the serious threats that America is facing with today is the burgeoning bureaucracy of Washington. The phenomenon of “administrative state” has been in the forefront of public debates for the last decades, however, their origins go back, at least to the progressive era. Can you shed some lights on the background of this phenomenon and can you also tell us why is it threatening the separation of powers along with the popular sovereignty?

R. B.: You raised a very good question because it does go back a long way. Our “republican Constitution” can protect the liberties of We the People only if it is followed. This is one of the reasons I defend “originalism” which merely says that “the meaning of the Constitution should remain the same until it is properly changed by a constitutional amendment.” The Constitution is the law that governs those who govern us. And those who are to be governed by it can no more change the law that governs them—without going through the amendment process—than we the people can change the laws that govern us without going through the legislative process.

But if the Constitition is not followed, then it cannot do the job of protecting the rights retained by the people. So the question is whether these independent agencies are following the Constitution or not.

The Constitution expressly contemplates in more than one place that there will be “departments” of the executive branch. And these departments execute or enforce the laws passed by Congress. Congress does not enforce its own laws. The problem, therefore, is not the existence of departments or agencies. Instead, the problem is whether these agencies or departments are simply executing—or administering and enforcing—the law that has been made by the federal legislature; or whether these agencies are themselves making law.

Since the 1930s, Congress has been passing very broad legislation that essentially set goals instead of creating rules of law for individual citizens to follow. As a result, the executive agencies rather than the legislature began to make the rules of law for individuals to follow, which went beyond enforcing and adjudicating the laws enacted by Congress. When Congress delegated its legislative power to the executive branch, that was a violation of the separation of powers that the original Constitution was designed to protect.

This is called the “nondelegation doctrine.” But the Supreme Court has not found an unconstitutional delegation since the 1930s. If it restores that doctrine and invalidates a law for improperly delegating legislative power, that would be “judicial activism” in the descriptive sense, but not in the pejorative sense. (Though I think we ought to drop the as confusing—because it two senses—and unhelpful because the term doesn’t explain why the invalidation is wrong or improper.)

L. S.: So the “administrative state” is looming on our constitutional horizon. What remedies could you envision for this dilemma? What could be the role of the Supreme Court?

R. B.: There are two ways we can change things properly in the United States. One of them is amending the Constitution. There is a movement to have a constitutional amendments convention—or convention of the states—that would try to address some of these problems. However, I think this is very unlikely to happen because two third of the states need to agree to call such a convention. The other way is for the Supreme Court to start enforcing the Constitution according to its original meaning.

One of the things the Supreme Court could do is to say that Congress cannot just delegate all their legislative powers to the executive branch and to the agencies. Congress needs to legislate themselves. However, as I said, the “nondelegation doctrine” has been more or less defunct in the United States since the 1930s. Although we have a few new Justices, at the moment we do not have a working majority of five or six Justices out of nine that are prepared to do much to restore the original meaning of the text. So whatever changes we will see are likely to be very incremental.

L. S.: Do you think there is a danger that the European Union is experiencing the same phenomenon?

R. B.: Knowing how mistaken are some about the U.S. political system, I hesitate to comment on the features of another system with which I am less familiar. So let me keep my comments at the most abstract level. The problem with the European Union from the perspective of separation of powers or “Federalism” and even of “subsidiarity” is that nation states are losing a lot of their independence with respect to making their own laws.

In addition, the European Union is an “administrative state” without real electoral or democratic accountability. Remember, I said above that the reason for electoral accountability—what we call democracy—is as a check on the abuse of power, not as an expression of the true “will of the people.” In Europe there are many “peoples” who find themselves increasingly unable to check the power of the central bureaucracy who are making the laws. Even the European Parliament does not have that much to do with the making of laws since the laws are made by the different agencies and committees. In some sense the European Union is an extreme form of the “administrative state” problem we have here and which is creating some of the problems with liberty. Like us, you have a legislature who is detached from the lawmaking being done by a bureaucracy that is difficult, if not impossible, for individuals or business to “check.” But we had best move on before I expose my ignorance of the inner workings of the EU.

L. S.: You just pointed out the heart of the debate that is going on in Europe. However, one might have to ass that a lot state constitutions in Europe are saying that they do not transfer sovereignty to the European Union; instead they are sharing the exercise of sovereignty with other Member States to the extent necessarily derived from the Founding Treaties. And in the United States states are not sovereign, are they?

R. B.: And I reject the idea that our states in the United States are sovereign. Unlike France, England or Hungary who are supposed to be sovereign, our states are not sovereign anymore; they became more perfectly unified in 1791 when the people (not the states) adopted the Constitution in popular conventions. But our states have what is sometimes called “divided sovereignty” in the sense that they have powers delegated to them by the people that the federal government does not have and the federal government has powers delegated to it by the people that the states do not have.

In the European Union, the governing powers were transferred directly from sovereign governments to a large “administrative state.” As I understand it, neither the Treaty of Rome nor the Treaty of the European Union was ratified by the respective peoples of the nations that comprise the Union. Unless the U.S. Constitution, it gets its powers from the member state governments. And right now I understand that your “administrative state” is increasingly overriding any remaining law making powers that your independent member states are supposed to have.

L. S.: Today, there is another dilemma closely related to the administrative state. There are increasing debates around the various interests embedded in this growing bureaucracy that are threatening the visible and democratic government. Although theories around a double government or “deep state” have been with U.S. since the “Gilded Age”, they recently became one of main themes of the political discourse. Do you see a parallel between the solidification of the “administrative state” and the “deep state”?

R. B.: I would say that the “administrative state” and the “deep state” are referring to two different things, but both result in problems. On the one hand, there are the NGOs (nongovernmental organizations) who are very powerful in Europe; and we have our own version of them in the United States. These NGOs are the ones that operate directly on or influence indirectly the administrative state, its the various agencies and committees. There is a loving relationship between the NGOs and the “administrative state” in Europe.

On the other hand, the “deep state” concept in the United States is somewhat different. The “deep state” is a concept to describe how the “career” agency personnel – government workers who are shielded by civil service protections – resist the policies of those who have been elected to govern them. The “deep state” is the permanent bureaucracy that can resist, sabotage or undercut the elected officials or the officials appointed by the elected President. What we see in the United States is “the resistance”—which is how they describe themselves—pitted against the Trump administration. This is a conflict between the permanent bureaucracy with their own agenda and the political appointees that are put in place by the elected President to constrain the permanent bureaucracy.

L. S.: In your view did the centralization contribute to this controversy?

R. B.: Absolutely! It is one of the reasons why businesses and corporations like centralized government because, that way, they only have one government to deal with. So in Europe, instead of negotiating with the English, French or Hungarian parliament, they can just go right to the source and get their favorite rules and regulations made by the European Union. This makes for one-stop-shopping for them. It’s the same in the United States.

But there are several problems with this one-size-fits-all approach. For example, with any policy, everybody has to live under the regime of whichever class becomes the ruling class; whichever class gains the reins of the power they get to implement their favorite. And, as you said at the beginning of this interview, this creates a kind of “Hobbesian” war. Instead of a “Lockian” society in which the government exists as the servant of people to protect the rights of individuals—each and every one of us—which I call the Republican Constitution, we now have essentially a “Hobbesian” vision of all against all. Once a “Leviathan” is created torul over everyone, you have to fight a “holy war” to control it or at least impede it because if you don’t control or impede it, then your political opponents will control it and with it they will control you. If pushed far enough, this is a recipe for either a hot or cold civil war in a society.

***

A cikk a Pallas Athéné Domeus Educationis Alapítvány támogatásával valósult meg.