Kellemetlen: elhangzott az eddigi legfontosabb mondat Magyar Péter rejtélyes videójáról

Bár a drogos bulibotrány nagyon zavaros, az biztos: Magyar Péter zsarolható – mutatott rá az elemző.

"Japanese judges do not seek to be the catalysts of social change. They believe in democratic institutions and thus defer to the democratic institutions of governance while maintaining, indeed reinforcing in their priority of values, the rule of law" - Professor John Haley pointed out in a conversation with Lénárd Sándor.

It is said that Japan has a harmony seeking society and harmony seeking social culture. Thus, one of the distinctive elements of the Japanese legal tradition is its unique approach to dispute settlement. How does it different from Western culture? What other characteristics are unique to the Japanese legal culture?

I would not say that Japan has a “harmony” seeking culture but rather a distinctively communitarian orientation. This orientation is, in my view, best understood in the context of two fundamental historical features.

The first is

Japan’s unique ethnic homogeneity.

Japan has never experienced any major migration from abroad since its early formation, nor until World War II any foreign conquest. Thus virtually all Japanese can be certain that all of their ancestors were present in the Japanese islands over two millennia ago. As a result, all of Japan’s institutions and cultural attributes developed internally, mostly by consciously borrowing from its more advanced neighbors.

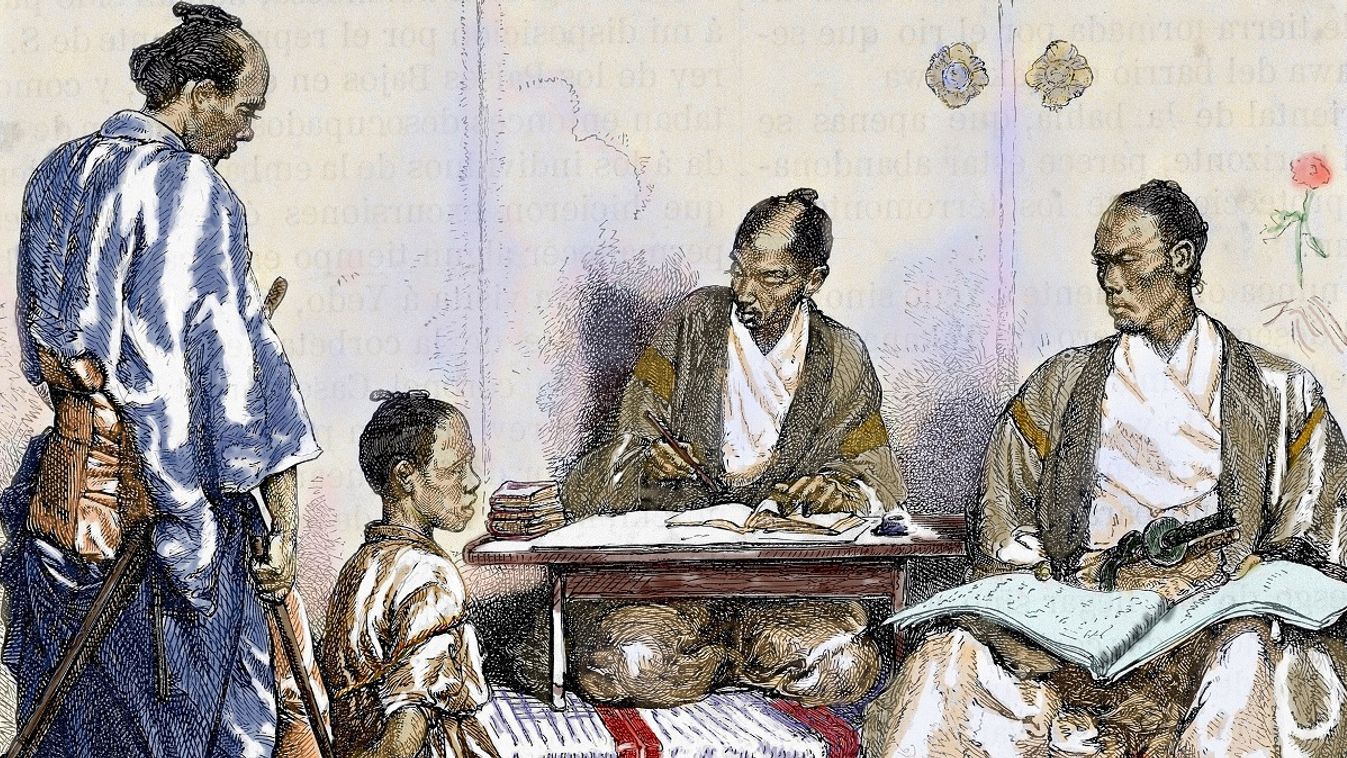

The second is the equally unique political and social restructuring that began in the 16th century and persisted for over two and a half centuries under Tokugawa rule. By the end of the 16th century hundreds of warrior lords who had emerged victorious at the end of the Ōnin War (1467–77) had established independent domains with central Castletown in which all members of the warrior class were required to live. The vast majority of Japanese lived in farming villages with restricted mobility and subject to domain authority but without direct oversight by often distant warrior officials. So long as taxes were paid and the domain regulations were not ostensibly violated—in other words, outwardly harmony prevailed—the villages were self-ruled. They became largely self-governing communities. Today nearly all public and private organizations from prosecutors and judges to banks and major manufacturers function as Japan’s contemporary villages with almost exclusively entry level, permanent employment but little if any meaningful alternative for exit until retirement. Employment is generally permanent. The result is

a community of lifetime employees.

Consensus-based decision making within these communities is the norm.

Since the era after the Meiji Restoration in the 19th century, ‘western jurisprudence’ was received in Japanese society. How has the Western influence changed Japan’s legal culture and way of life and how it is able to defend it?

Historically, as noted previously, Japan’s first laws and political institutions were based on Chinese sources. It was borrowed from the Tang Dynasty and legal institutions – even its written language – were borrowed. Beginning with the introduction of Chinese language during the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC – 9 AD) and law in the 7th and 8th centuries during the T’ang Dynasty (618 AD– 907), Japan’s rulers have consistently looked to institutionally advanced neighbors for models to replicate and adapt. Not surprisingly during the second half of the 19th century as Western Europe and North America emerged from the Industrial Revolution as the world’s foremost economic and military powers, Japan sought to emulate their successes. The consequence was the transformation of Japan’s economic, political, and legal institutions. Japan entered a new era under its new laws and institutions. In a sense Japan was fundamentally transformed by its own reforms.

We need to keep in mind that

the sources may have been Western, but they became Japanese.

Japan Civil Code may have been based on drafts of the German Civil Code, promulgated in 1896 and 1898 it preceded the enactment of the German Code of 1900. The courts’ recognition of the rights of unregistered wives after a valid marriage ceremony as well as non-code security interests in the first decade of the 20th century as enforceable judicial precedents illustrate the enlightened independence of Japan’s transformed judiciary.

Many basic traditional communitarian values, habits, and expectations adapted to the new regime. Seldom did disputes within families or even individual business enterprises become public. Most were resolved within the community. Actions by judges and law enforcement official also reflected basic cultural values.

Procedures were enacted to allow judges to act as mediators to resolve by compromise before formal decisions were to be handed down.

Even more remarkable, police and prosecutors refrain from reporting or prosecuting offenders who express remorse and make reasonable efforts to compensate any victims of their crimes. Even if formal charges are brought and, despite the offender being found guilty in over 95 percent of all cases, judges routinely suspend sentences for those who similarly express remorse and have attempted to compensate victims. Retribution is not a Japanese cultural characteristic. Today, whatever the origins of Japanese law and other institutions, they are as Japanese as sake, sushi, and Subarus.

The concept of human rights is known in Japan too, but they have a quite different reading including the requirement of the “consideration of others” so that people need to respect rights vis-á-vis their fellow citizens. How do Japanese people view the relation between the state and its citizens?

With respect to the legal rights of citizens vis-à-vis the government, Japan, in my view, does not differ in comparison with other industrial democracies, except that the

Japanese government seems to be less intrusive in the lives of its citizens.

Social order is maintained principally as a result of community obligations not legal rights and duties.

So, the Japanese society does not share the currently prevailing conception of human rights in Western societies… Do Japanese people relate to the principle of “do not do unto others what you do not want others do unto you”?

My understanding is that “rights” relate to legal relations among private parties, such as contracts and governmental institutions, such as right conferred by statute. In this sense, Japan does not differ. However, Japanese society is also and perhaps more significantly order by conceptions of social obligations of family and community.

Due to the distinctive features of the Japan’s historical experience there is a relative lack of a widely shared belief among the Japanese in universally applicable moral imperatives. In political discourse, contested social and political issues from property rights to human rights are rarely if ever cast in terms of overlapping moral and legal imperatives. Instead of any shared belief in universally applicable, transcendental absolutes,

Japan is notable for its distinctively contextual communitarian orientation and emphasis on consensus

as a shared social value. Community norms, not transcendental norms, are what matters.

Based on the societal characteristics you have described, is there a unique Japanese way of life? If so what can be the virtues and values that belong to this way of life?

The simple answer is “yes”. As I indicated before, Japan is unique in its homogeneity, ethnic and cultural. Its

communitarian orientation is equally unique.

In the terms of constitutionalism, the Constitution adopted after the Second World War meant a disruption. How could the country preserve its constitutional identity? Has the Japanese judiciary resort historical constitutional sources when they interpret the Japanese constitution?

I would not describe Japan’s postwar constitutional order as a “disruption”. Continuity seems to be a more accurate term. Unlike Germany where with surrender US, British, French or Russian military officers were placed in charge of every city, town and hamlet, in Japan no civilian officials were replaced except those at the highest levels of the national government. All Occupation reforms may have been “suggested” or recommended by Occupation authorities, but they were enacted pursuant to existing law by a newly elected parliament.

Thus unlike Germany these reforms were legislated as domestic law and unless repealed or amended remain in force today.

The postwar constitution has continued in force without a single amendment for three quarters of a century, nearly two decades longer than the Meiji constitution.

What can be considered as part of the constitutional identity of Japan? Does the Supreme Court of Japan defend these values and how does the Supreme Court approach the historical legal sources and achievements of Japan in general?

In my view, judges in Japan share the prevailing communitarian orientation of their society, an orientation that rejects Manichean choices and moral or ―scientific‖ absolute. Instead both the career judges who staff all of the lower courts as well as the Justices of the Supreme Court rely on their collective and individual perceptions of community values shared by peers. The standards used by Justices—both to define their appropriate role as well as to reach the most appropriate outcome - differ, and more often than not remain implicit. Judges and Justices seem to agree, however, that reaching a - sensible decision is paramount.

Justices try to formulate their decisions in ways that parallel the “sense of society”. Indeed, the phrase ―

) has long been the most commonly used rationale for judicial decisions.sense of society (shakai tsūnen) has long been the most commonly used rationale for judicial decisions.

Judges do not explicitly define their role in choosing or determining what is the best or most appropriate outcome with rationales based on their view of the most ―reasonable‖ or morally appropriate outcome. They too function within the same historical and social contexts as other members of the society. History and shared experience similarly shape their values and beliefs. Individual political ideologies surely differ, but it would be remarkable for career judges generally to be less or more center-right in their personal predilections than the Japanese electorate as a whole.

They also, I believe, accept an unstated premise that legislative and administrative decisions reflect a consensus among the participants instead of a simple majority. The issue remains as to who participates—who sits at the table—but the political and administrative processes do not routinely require merely fifty-one out of a hundred votes. As a consequence, judges are cautiously conservative. They adhere to precedent and endeavor to maintain, as best they can in a changing society, a legal order that is predictable and consistent.

Stability is a virtue, not a vice.

They do not seek to be the catalysts of social change. They believe in democratic institutions and thus defer to the democratic institutions of governance while maintaining, indeed reinforcing in their priority of values, the rule of law.

Article 9 of the Constitution that bans Japan from maintaining armed forces is one of the most controversial provisions, especially under the shifting geopolitical circumstances. How do you see the debate unfold around this provision?

The devastation of World War II helps to explain why the issue of a military establishment in Japan—either foreign or native—remains one of the two dominant constitutional issues of the postwar era. Since 1947,

Japanese courts have adjudicated at least two dozen cases related to the constitutionality of various measures under Article 9.

They have included direct challenges to the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty, the presence of U.S. military bases, and the Self-Defense Forces. However, the constitutionality of the U.S.-Japan security arrangements and the maintenance of U.S. military bases in Japan have been confirmed multiple times. All fifteen Justices of the Supreme Court agreed that, under Article 9, Japan retained a fundamental right of self-defense and could enter treaties for mutual security.As confirmed by judicial decisions and practice, today

Japan maintains a defensive military force second only to the United States in conformance with Article 9.

In 2015 the Diet enacted legislation that permits the Self Defense Forces to aid allies engaged in armed conflict. However, two years later efforts by the Abe Government to amend article 9 to explicitly allow such actions failed.

What are the constitutional and geopolitical challenges the country is facing?

To my knowledge Japan today is not subject to any extraordinary domestic political or economic issues except the international economic concerns shared by other industrial democracies. Japan is, however, subject to the military threats from China toward Taiwan and the surrounding seas. Its responses remain in coordination with the United States.